Those who know me personally are already aware that I, like many, have been sucked well and truly into Harry Potter fandom (I have my sister to blame/thank for this). Although many people have disregarded it as “just a kid’s story”, like I once did, I’ve found that the more I read these books, the more intricate details I have noticed about them. From a critical perspective, it’s interesting to note how Rowling relies upon duality and opposition, and upon parallels and foreshadowing, to construct the narrative of her series. In this series of posts, I will briefly discuss a few of these, referring to relevant volumes from Rowling’s text where necessary. I’m not going to get all technical; I just thought this would be fun. I’ll dabble in semiotics and structural analysis, undertake a few explorations of certain themes, and unite a few fan theories along the way if I can.

So, in case it wasn’t already obvious, this post is full of ***spoilers*** (although I doubt there’s many people left in the world who don’t have a basic working knowledge of the plot by now!)

Part 2: Dual Cores, Dual Characters

The battle raging between Harry and Voldemort is the main event, the primary narrative arc of the entire series. It’s unsurprising, then, that the complex duality Rowling creates between these two characters resonates throughout each of the books in a number of different ways. Two of the main structural mechanisms used throughout are that of symmetry and opposition. This post intends to explore Rowling’s usage of both in the construction of the relationship between Harry and his nemesis.

Firstly, it is important to note that the similarities between Harry and Voldemort are striking. They are both half-blood wizards (although their parentage is inverted, with Harry having a Muggle-born mother and wizard father, and Voldemort having a witch mother and Muggle father), who grew up without their parents, only discovering their wizarding heritage at age 11.

Both are similar in appearance, with their dark hair and slim physique. The wands they select (or, in fact, are selected by) both contain feathers taken from the same phoenix, Fawkes. Both are known readily to the public, and often by a title other than their name – Harry is The Chosen One, or the Boy Who Lived, and Tom Riddle disregards his Muggle father’s name in favour of the title Lord Voldemort. His Death Eater followers know him as the Dark Lord, and to the wizarding public, he is You-Know-Who or He Who Must Not Be Named.

Harry has a gang of followers, like Voldemort – firstly, he assembles the DA, and he is followed by the Order of the Phoenix as their leader and rallying point after Dumbledore’s death. Like Voldemort, he is able to summon and instruct them (using the Galleons with the protean charm cast on them – Voldemort, of course, uses the Dark Mark).

Harry and Voldemort are both charming enough to retrieve information from highly unwilling people, such as the Grey Lady and Horace Slughorn. Both can speak to snakes. Both discovered all of the secrets of Hogwarts Castle, where others had not. They share each other’s minds. They share the same blood. Rowling has deliberately created clear symmetry between her protagonist and antagonist, and draws attention to it repeatedly throughout her books.

However, Harry is, of course, presented as Voldemort’s absolute opposite, in that he has chosen the side of good rather than evil. They are thus presented in continual opposition. This is, I think, symbolised quite nicely by the seven Potters and seven Horcruxes in the seventh book. Hermione asserts, when explaining Horcruxes, that a Horcrux is the “complete opposite” of a human being.

So, whereas Voldemort occupies the inside of his seven Horcruxes, Harry is present externally in seven forms (as several characters transform into him using Polyjuice potion). This inside/outside opposition is one of many dichotomies created by Rowling to symbolise the battle between good and evil. Another is the opposition between love/hate, with love being Harry’s greatest weapon, according to Dumbledore, and Voldemort’s greatest weapons (the unforgivable curses) being fuelled by hatred – Bellatrix Lestrange says as much in the fifth book.

Perhaps the most prolific, though, in terms of a semiotic analysis, is the contrast formed in the text between the colours red and green – red symbolising anything Harry-related, and green symbolising anything Voldemort-related. These are, of course, the colours of Gryffindor and Slytherin Houses respectively, and this distinction between Harry as red and Voldemort as green is underlined continually.

Note how Harry’s signature spell – ‘expelliarmus’ – emits red light from his wand, whereas the ‘avada kedavra’ curse used so often by Voldemort creates a burst of green light. Fawkes, a red phoenix, is Harry’s defender in the Chamber of Secrets against the Basilisk, a green snake. When Harry seeks a way to destroy Voldemort in the cave with the Inferi, he takes what he needs from a basin containing Voldemort’s green potion. When Voldemort desires the protection of Harry’s mother’s sacrifice as a means to destroy Harry, he seeks what he needs within the red blood of Harry’s arm.

Godric Gryffindor’s sword – the magical artefact symbolising Gryffindor House, the only House-related relic Voldemort never succeeded in obtaining and transforming into a Horcrux, the object used by Harry to destroy both of Voldemort’s snake-related Horcruxes and the Basilisk – is inlaid with red rubies. The relation between Harry and the sword is reinforced further by the fact that the sword, like Harry, only imbibes that which makes him/it stronger. Just like the sword takes venom from the Basilisk but resists dirt and dark magic, Harry, too, takes what he needs from Voldemort’s mind/soul without ever being corrupted by evil. Yes, he can see what Voldemort is doing and knows what he is thinking, but unlike Voldemort, he is not encouraged towards undertaking a mission to avoid his own death – he decides not to pursue the Hallows as a way to become the ‘master of death’, and instead dies to protect his friends.

In doing so, he actually does become the master of all three Hallows and ensures his survival, and his enemy’s demise. In complete opposition, it is Voldemort’s pursuit of immortality that means he is no longer properly alive, and that he cannot kill his enemy.

The prophecy regarding Voldemort and Harry – specifically the phrase “neither can live while the other survives” – is particularly significant, I think, in this regard. The most obvious translation is the one that Harry asserts – that one of them will have to kill each other in the end, as Voldemort will continue to pursue him until one of them ends the battle.

However, it would also be accurate to say that neither can die while the other survives, as Harry acts as a Horcrux for Voldemort, tying him to life, whereas Harry’s blood runs in Voldemort’s veins after his resurrection, and this ties Harry to life, too (note how, again, Harry resides in the flesh, on the outside, whereas Voldemort is hidden deep within Harry, on the inside, as a fragment attached to his soul).

It perhaps makes more sense, then, to read this part of the prophecy as being more subtle… “neither can live” (i.e. they both have to die) “while the other survives” (i.e. whilst that piece of the other lives on within them). To truly kill Harry, Voldemort would have to discard his living body (and therefore ‘kill’ the blood keeping Harry alive), and as we know, to kill Voldemort, Harry has to let himself be killed (to destroy the bit of Voldemort’s soul living within him).

Their rises and falls in power and influence are inextricably linked in inversion, too. The destruction of Voldemort’s body coincides with – indeed, it actually causes – Harry’s gaining of additional powers. Voldemort’s rise to power corresponds with Harry’s loss of the powerful and helpful figures in his life (Sirius and Dumbledore in particular).

The resistance gain momentum as Harry diminishes Voldemort’s power through his destroying of Horcruxes, but as Harry dies, they are weak and mourning their dead (again, the love/hate dichotomy arises – Rowling often uses the concepts of love and grief as if they were synonymous… perhaps they are, but that’s a question for another day). Harry’s revival coincides with their defiance and resistance – as they are now protected by his sacrifice – and they are able as a singular force to reduce Voldemort to his weakest state… that of Tom Riddle. Harry’s final triumph is, of course, Voldemort’s defeat.

So, as this deconstruction has shown, certain ideas and dichotomies echo throughout Rowling’s Harry Potter series, and all this adds to the overall enjoyment and experience of the books.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Ok, more to come on this in further posts – as ever, please feel free to share your thoughts below!

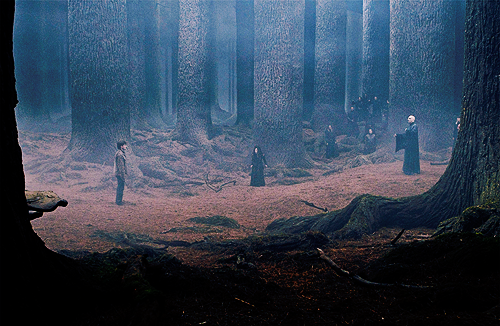

(Images: Warner Bros. Studios)

another excellent post on this subject and a fun read. Rowling used the heroic arc for Harry too – originally when the series came out, I read them aloud to my two girls and though we greatly enjoyed the stories I never ranked her near Tolkien or C.S. Lewis – but you’ve helped me see that

she built these stories on a complex and rich foundation.

Harry and Voldemort – separated by a mother’s love.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Harry and Voldemort – separated by a mother’s love”

What a wonderful way to put it! 🙂 Thanks for your comments, thank you enjoyed the post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will there be a part 3 ?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, indeed there will, as soon as I get around to it! Got a few more posts on HP up my sleeve. Think I’ll look at etymology next. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another fine analysis that I enjoyed very much: and of course another parallel between Harry and Voldemort is that both are resurrected from death or half-life, Voldemort by Pettigrew in the cauldron, Harry after his death at the hands of Voldemort himself.

By the way, I’m pretty sure that should be ‘horcrux’ with an ‘r’. I’m guessing that Rowling, with her degree in languages, was playing on French ‘hors’ (outside) and ‘crux’ (a cross, perhaps here symbolic of grave crosses, among other things), suggesting life outside the body.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re absolutely right – that’ll teach me to AutoCorrect when I’m fall asleep! 🙂 Thanks!

LikeLike

I’m actually planning on doing a post on etymology in the series, is it OK to include this observation? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, no problems. I haven’t noted this etymology anywhere else, but it’s of a piece with her other puns, such as with the Pensieve. (By the way, I think this should be pronounced as in ‘pensive’, derived from the French for thought plus ‘sieve’, i.e. it’s a device for sieving thoughts. In the films it somehow rhymes with ‘sleeve’, which is not at all how sieve should be spoken.)

LikeLike